The Journey of Prints: Exploring India’s Trade, Craft, and Design Legacy

Aparna Sridhar | 9 October, 2025

The Marwar Block Print Revival Project is advancing on multiple fronts to reclaim what was lost over the past century — not just the prints, but the rich cultural and design history of Marwar, a desert region in western Rajasthan bordering Sindh to the west and Kachchh to the south. These geographies have shared a remarkable exchange of knowledge, which we continue to trace and document. In the coming months, the project aims to print and publish 400 lost designs that reflect the community identity of Marwar.

Presently this project is supported by the Centre for Embodied Knowledge (CEK), Samagata Foundation, Neo Foods Private Limited, and Kota Heritage Society (KHS).

Dr Madan Meena, Independent artist and Folklore Researcher, offers a 400-year historical perspective on Indian textile design, tracing the shift from hand-painted to printed textiles. While trade textiles from centers like Ahmedabad, Machilipatnam and Sindh have been well preserved due to their economic value and refinement, rural textiles remain under-documented and poorly conserved.

Recent Discoveries and Research Highlights

A major discovery in Jodhpur region revealed a collection of 40 chunks of textiles encompassing over 100 designs. Another breakthrough was identifying a previously unknown textile printing center in Pipar, which preserved nearly 1,000 designs indicating deep historical ties to 17th-century Ahmedabad. These finds shed new light on regional trade networks connecting Ahmedabad, Khambhat, and other centers.

Fieldwork and Documentation

The current project aims to catalogue 400 textile designs by October, supported by a 25-lakh-rupee fund and local patronage. The research emphasizes oral histories, community engagement, and verification through multiple field visits. Documentation includes both technical and cultural analysis, ensuring a holistic record of indigenous textile knowledge.

Global and Cultural Context

Dr Meena situates India’s textile innovations within a global framework, noting the country’s advanced use of natural dyes and printing techniques compared to other regions. He highlights the influence of Persian artisans and the historical exchange of textile knowledge between Kashmir, Ahmedabad, Banaras and Sanganer.

Indigenous Knowledge and Design Philosophy

He underscores the need to recognize indigenous knowledge systems alongside formal disciplines, drawing parallels with Ayurveda’s evolution. His design philosophy draws inspiration from botanical studies, wall frescoes and cultural context, viewing textile design as a living art connected to music, painting, and philosophy. Block printers, he notes, are active interpreters and innovators in this creative continuum.

Activism and Advocacy

Dr Meena’s work extends beyond research into activism – focusing on minority, endangered, and lesser-known crafts. He advocates for authenticity, challenges misinformation, and seeks to restore dignity and visibility to marginalized artisan communities.

Detailed interview

What is the most significant discovery in this particular phase of research?

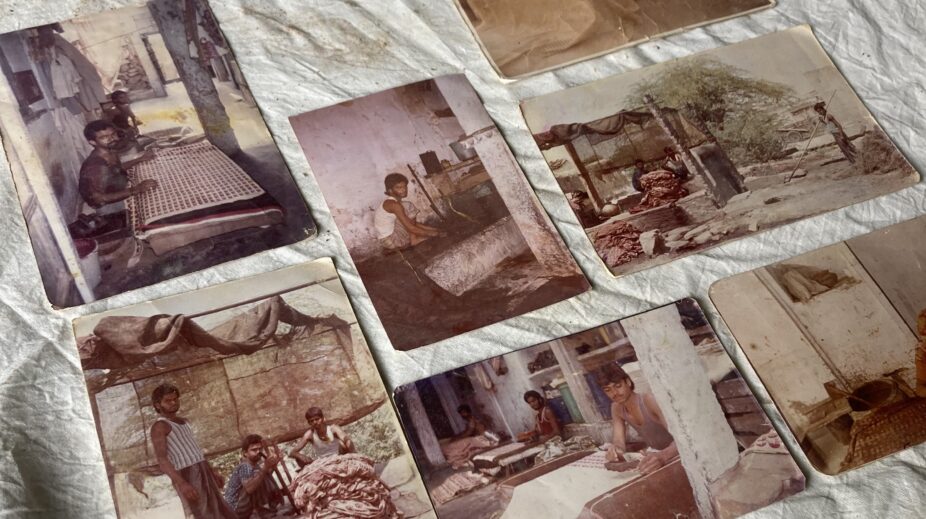

I was very fortunate to collect a significant set of textiles from dealers in Jodhpur, Kachchh and Jaipur. Another was an important trip with block printer Ranamal Khatri to the block printing centres south of Barmer which closed down in the 1960s-70s. This resulted in a collection of some 100 discarded blocks dating back to 100 to 150 years. My current target is to document four hundred designs, but the scope is already expanding beyond that.

An unexpected discovery came from Pipar — a center that few would recognize or even believe existed. This finding emerged through my ongoing research, which connects Pipar, near Jodhpur, with Ahmedabad. Historical links between these two centers go back nearly 200 to 300 years, possibly even to the 17th century. Both regions were home to the Nagauri Chhipas, a community of textile printers who converted in the 14th century in Nagaur in Rajasthan and maintained strong ties ever since — through trade, travel, and matrimonial relationships.

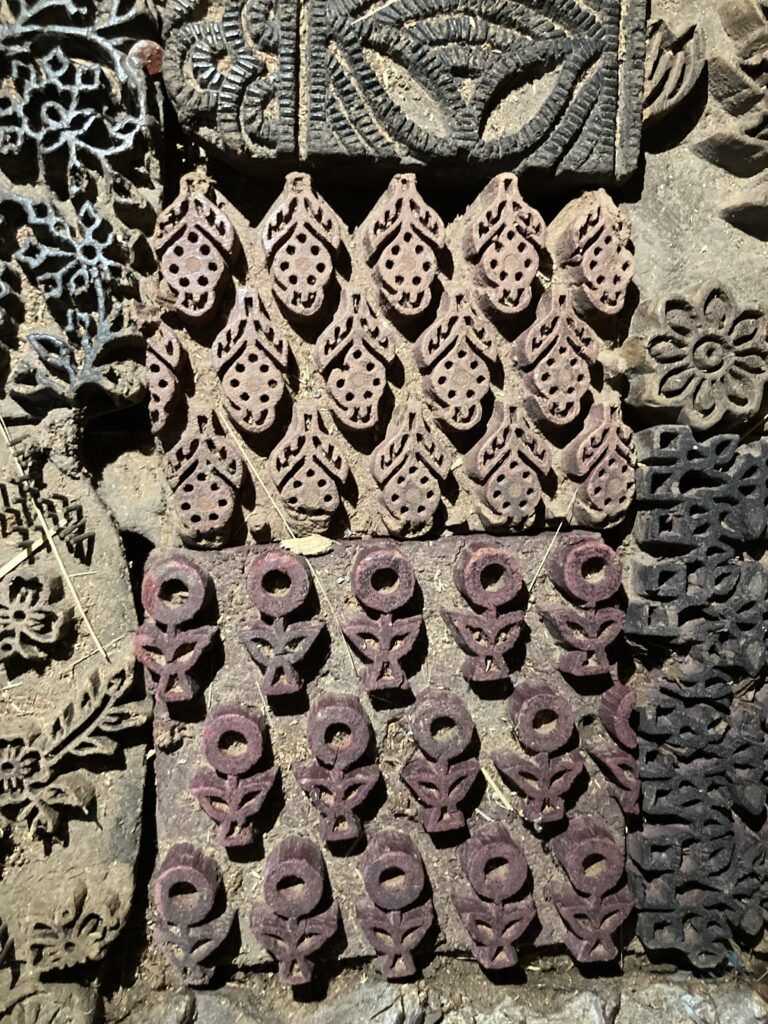

Production in Pipar was initially very small-scale. Most block-printing centers I studied primarily served people within a 10 to 15-kilometer radius, as neighboring areas had their own centers for local demand. However, the blocks discovered in Pipar reveal a much larger story. I found them with five families who had stopped printing but had carefully preserved their blocks. One family alone possesses 500 blocks, representing roughly 1,000 designs, all originating from Ahmedabad-descended families.

These blocks were used locally in Pipar, but they also had direct connections to trade textiles printed in Ahmedabad and other centres of Gujarat. Some blocks existed simultaneously in both Ahmedabad and Pipar, and these families were producing textiles for export, sending them further to ports for international trade. This network highlights how Pipar was not just a small local center, but an important node in India’s historical textile trade.

In the 17th century, Ahmedabad’s textile samples became renowned, many of which are now housed in museums or showcased in international exhibitions. Trade textiles from Ahmedabad, known as Saudagiri prints, were exported through the port of Khambhat, reaching markets in the Middle East and Central Asia. Until recently, it was widely believed that these trade textiles were produced only in Ahmedabad. Pipar’s preserved blocks show that it was also engaged in high-quality textile printing for trade, participating in the same commercial networks as Ahmedabad and contributing to India’s larger textile exchange.

Where was the origin of the prints?

The patronage for textile prints in Ahmedabad was very high, largely due to its thriving trade and wealthy clientele. Pipar, on the other hand, has always been a small village and not a major textile center. However, because of its historical connections with Ahmedabad, Pipar was occasionally outsourced to print Ahmedabad’s designs. This is why we now see such intricate designs appearing in Pipar.

Ahmedabad itself is an old city, historically known as Ashaval (or Ashapalli), with a long history of textile production, both in printing and weaving. Over the centuries, the designs there evolved to become highly intricate. Knowledge and techniques from Ahmedabad were shared among printers, and these textiles eventually travelled far, even outside India. Pipar remains unique in showing these designs locally while also linking to international trade routes.

I was fortunate to collect a significant set of textiles in Jodhpur, Kachchh and Jaipur. Some very old prints and blocks were obtained from a few dealers and printers there. Initially, only one family in Pipar had preserved blocks, but to speed up documentation and production, I have now involved more families. Monsoon had temporarily halted production, but it has now resumed, and I have received four recently printed textiles to document and showcase.

What is the time period in history that has been covered in your research?

The history of textile production in India spans at least 400 years. If we take Ahmedabad as an example, its textile tradition is even older, and Sindh’s history predates that further. Studying printed textiles like Ajrakh reveals years of refinement in design and technique. Over time, a clear shift occurred from hand-painted textiles to printed textiles, especially along the coastal regions. This transition is well documented because many of these textiles were produced either for temples or for trade, which ensured their preservation.

Unfortunately, rural textiles were rarely preserved. They were often recycled or repurposed, so fragments of these designs are rarely found today. As a result, rural textiles carry only a limited historical record – perhaps hundred to two hundred years at most – and their designs are generally basic.

In contrast, textiles produced at major centers like Machilipatnam, Ahmedabad, or Sindh were far more refined. They were created for noble class and trade and had significant economic value, which drove innovation and intricate design work. These trade textiles are markedly different from rural textiles; the styles, motifs, and sophistication of designs do not match the simpler patterns found in village production.

What is the next stage of the research?

Currently, the project has enough funding to sustain operations for the next three to four months. The collection of designs continues to grow, but community-level knowledge still requires field visits. So far, documentation has mostly been with printers, not with the broader community that historically used these textiles. This research will continue until publication, because knowledge evolves in layers – new connections and insights emerge over multiple interactions rather than a single visit.

I am also sharing documented designs with other printers. For example, designs documented in Pipar, Jodhpur and Barmer are shared with Kachchh, which generates new insights and helps trace variations across regions. The immediate goal is to prepare a catalogue of all 400 designs by the end of October so that the information is ready for broader dissemination and further fieldwork.

What is your main mode of research?

Here is how I approach my study. I do not rely heavily on books, though I do consult some research articles and scholarly works that provide solid reference material. Most of my knowledge comes from oral histories, which I cross-check rigorously. It is never enough to take information from a single person — verification across multiple sources is essential. Based on these oral accounts, I form my own interpretations.

When specific historical names or events are mentioned, I refer to historical texts to verify dates, conversions, and other contextual details. This ensures that my understanding is grounded in both oral and documented history.

When analyzing a textile, I do not begin with the print. I first examine the construction of the cloth to determine its age and origin. This includes studying the spinning of the yarn, the type of weaving, and the thickness of the fabric — which can indicate where and how the cloth was produced and worn. I also study the colors and natural dyes used, identifying which regions or communities traditionally employed specific dyes and hues. Similarly the old blocks speaks a lot, not just the patterns but its quality of carving and shape of the handle. By combining technical analysis with historical and oral research, I can gain a comprehensive understanding of each textile piece.

If we compare similar developments in textiles around the world during the same period, how would you assess India’s position? Where does India stand in terms of innovation, refinement, and trade in textile production?

India was far ahead in terms of printed textiles, natural dyes, and hand-painted textiles during that period. Almost no other region in the world had reached the same level of sophistication, except Iran, from which many Indian textile techniques, including block printing, were influenced. India developed its own unique motifs and designs; for example, the Farrukhabad block-printing center produced designs entirely distinct from those in Gujarat, with very few motifs overlapping — except for common motifs like the paisley, which appears widely in weaving, printing, and embroidery.

The arrival of Persian artisans to Kashmir catalyzed a flow of knowledge and skills. These artisans spread their expertise from Kashmir to Ahmedabad, and later some moved to Banaras. During a recent visit to Banaras for a Ministry of Textiles project, I studied traditional looms and documented them using local terminology. This allowed technical verification: drawings and loom terminology sent to Ahmedabad confirmed the same practices were in use there. Thus, oral histories were verified through technical analysis.

Historically, many of the earliest master weavers were Muslim, though over time Hindu artisans also contributed significantly. Banaras became a melting pot for artisans from all religions, castes, and philosophical traditions. The city’s temples, palaces, and community centers attracted skilled artisans, who brought their craft knowledge with them. This continuous exchange of people and techniques helped many crafts in Banaras evolve, creating the rich, multi-layered textile traditions we see today.

How beautiful it would be to see the movement of textiles.

The work is always guided by demand and need. For example, I discovered a story about a ‘Satara’ textile that was once exported to Yemen from Pipar. A young printer Ayub Chhipa mentioned that the designs on these textiles matched images which he had seen online of a woman in Yemen wearing a similar motif. I learned that the textiles had been sent through a particular family. During a visit to Ahmedabad, I was able to locate this family and track the original textiles, acquiring one piece for myself — a textile that had actually been sent to Yemen. The exports stopped about four years ago due to disturbances related to Ukraine, and the workshop that handled these exports has since closed. These were the last printers still sending textiles abroad.

This is how stories emerge, and how the research journey unfolds. On another visit, I encountered a different printer with a large collection of Saudagiri prints. Among those prints, I was able to identify many designs that are now part of my collection from Rajasthan.

In India, we often categorize artists into two groups: those shaped by markets and galleries, and those rooted in villages who remain largely invisible in the intellectual mainstream. Do you think this division still exists today?

Yes, there is always a division. Contemporary artists emerging from established institutions are privileged because they fit seamlessly into existing networks. In contrast, artists from rural or less-recognized backgrounds often face two major challenges: lack of authentication and the insecurity or resistance of the formal sector toward them. Breaking established notions is always difficult, and as a result, these artists are often neither promoted nor welcomed in mainstream circles.

I have observed this firsthand. For example, I was invited to give a lecture under an IPs program. While they expected me to speak about IKS in a conventional way, I wanted to focus on indigenous knowledge and the Indian knowledge systems. When I proposed my topic as “Indigeneity of the Indigenous Knowledge Systems,” they completely disagreed. Despite being institutions that present themselves as progressive, leftist, or socially oriented, they were uncomfortable with the topic.

I wasn’t criticizing the established system; I only intended to highlight how indigenous communities live, imagine, and contribute to the world. My focus was entirely on the positive aspects of these communities and their knowledge, yet the mainstream felt threatened by it. This reveals the ongoing insecurity and resistance toward acknowledging non-formal, indigenous knowledge systems.

Indians have developed their knowledge systems deeply in connection with nature. Their evolution of knowledge comes from being nature worshipers, where their deities are not merely idealized mythical figures but living entities whose actions and moods can be challenged. In traditional Hindu practice, one could question or appeal to a deity like Kali if a problem was unresolved — something we rarely see today. Issues were often addressed by shamans or local guides, sometimes dismissed by the formal system as superstition. Today, modern society might not believe in these practices, dismissing rituals, charms, or folk remedies as irrelevant.

Yet, even in a highly scientific era, mythology continues to hold relevance. IIT professors, IT professionals, and scholars still reference these ideas. Why then is there skepticism toward indigenous knowledge? Why does such discrimination persist?

Indigenous communities were the first to interact with the natural world — determining which plants, fruits, or substances were edible, poisonous, nutritious, or medicinal. Their observations and experiences formed the basis for Ayurveda, which was later formalized and textualized. The knowledge was tested, refined, and systematized over centuries, yet much of it remains oral and unrecorded. This knowledge cannot simply be disregarded, because it represents centuries of lived experience and empirical observation, even if it doesn’t fit into the formal scientific framework.

From this research project can we derive a design philosophy for textiles?

Because I am a painter, I have an understanding of how to formalize any figure or shape. I can render it realistically, abstractly, or minimally. When I look at a motif in a block, I always ask myself: How did this motif evolve? What journey did it take to reach this form? This has been a constant query whenever I meet block carvers.

I also draw inspiration from British botanical illustrations, which are highly realistic and were created to accurately identify plant species — studying leaves, flowers, seeds, and every detail. The block carvers, in their own way, have conducted a botanical study through design, translating nature into motifs.

Currently, I am planning a study where a traditional miniature artist, an illustrator and I will work with block carvers to reinterpret botanical illustrations into block prints. This requires understanding how the realistic study of plants can be transformed into artistic motifs suitable for printing from artisanal imagination.

This approach reflects my design philosophy: to understand the evolution of motifs, to decode the visual language embedded in traditional practices, and to reveal the underlying philosophy that informs architecture, prints, paintings, and craft. This philosophy is deeply embedded in the creators’ DNA, and our task is to interpret and preserve it through research and practice.

CONCLUSION

This project explores India’s historic block-printing traditions, tracing designs, techniques, and indigenous knowledge across regions like Jodhpur, Pipar, Ahmedabad, and Sindh. Dr Meena has collected rare textiles – from 40 pieces in Jodhpur with over 100 designs, 100 blocks from south of Barmer, and blocks in Pipar representing 1,000 motifs. Pipar, once considered a small local center, emerges as an important node linked to Ahmedabad’s trade textiles, which were exported internationally.

The research combines oral histories, technical analysis, and historical verification. Textiles are studied for fiber, weaving, and natural dyes before analyzing prints, and oral accounts are cross-checked with historical texts. India’s printed textiles and natural-dye traditions were globally advanced, influenced by exchanges with Persian artisans and movement of knowledge between Kashmir, Ahmedabad, and Banaras.

Dr Meena’s design philosophy focuses on tracing motif evolution and translating botanical studies into block prints. By October, the project aims to document 400 designs in a catalogue, preserving this living heritage and advocating for recognition of indigenous knowledge systems in mainstream discourse.